| gence of the modern state with its agencies for collecting

information on its citizens and their activities, and the theoretical interest

of political economists in finding causes for human social behaviors. These

“three movements,” Walker wrote, were pulled together in the career of

the mid-l9th-century Belgian astronomer-statistician Lambert-Adolphe-Jacques

Quételet, widely regarded as the founder of modern social statistics.

In 1841 Quételet organized Belgium’s central statistical bureau,

which became a model for similar agencies in other countries, and his international

leadership in statistical research continued until his death in 1874.

Nineteenth-century

scholars trying to make a science out of the study of human behavior faced

a dilemma: the model science of those days was classical physics, with

its deterministic laws describing natural phenomena, but human behavior

seemed individual and indeterminate. Quételet’s resolution of the

problem bypassed the question of the individual with the concept of an

“average man.” He showed that whereas there are no laws determining individual

behavior, there are regularities in the attributes and behavior of groups,

and that these regularities could be characterized mathematically by the

laws of probability. Quételet was convinced that even menial and

moral traits, if only they could be measured accurately, would also follow

regular laws of statistical distribution.

Quételet’s most original

and most startling work was his analysis of the influence of such factors

as sex, age, education, climate and season on the French crime rate (1831).

The data did not allow a prediction of who would commit what crime, but

according to Quételet they did display regularities that would enable

a scientist to “enumerate in advance how many individuals will stain their

hands in the blood of their fellows, how many will be forgers, how many

will be poisoners.” The discovery of these regularities led Quételet

to the radical conclusion that “it is sociely which, in some way, prepares

these crimes, and the criminal is only the instrument that executes them.”

Although Quételet’s work

was highly regarded by many scholars, it was abhorred by others. The determinism

of his “social physics” was an anathema to people committed to the prevailing

doctrines of free will and individual responsibility. John Stuart Mill,

for example, wrote at length against probability in general and its application

to social science in particular. Another vocal opponent of the statistical

view of man and society was Charles Dickens. His novel Hard Times

was meant to satirize those people, Dickens later said, who could see nothing

but “figures and averages,”

133 |

those “addled heads” who would use the yearly average

temperature in the Crimea “as a reason for clothing a soldier in nankeens

[silks] on a night when he would be frozen to death in fur.” Dickens disliked

the statistical view because he thought it was dehumanizing, and in Hard

Times he portrayed the regularities found by statisticians in the rate

of insanity, crime, suicide and prostitution as a “deadly statistical clock.”

Nightingale, on the other hand,

was an ardent admirer of Quételet’s work, and she early displayed

a predilection for collecting and analyzing data. At Scutari,

apart from the all-important sanitary reforms she instituted, she also

systematized the chaotic reord-keeping practices; until then even the number

of deaths was not known with accuracy. When she returned to England in

1856, she met William Farr, a physician and professional statistician.

Under Farr’s guidance Nightingale soon recognized the potential of the

statistics she had gathered at Scutari, and of medical statistics in general,

as a tool for improving medical care in military and civilian hospitals.

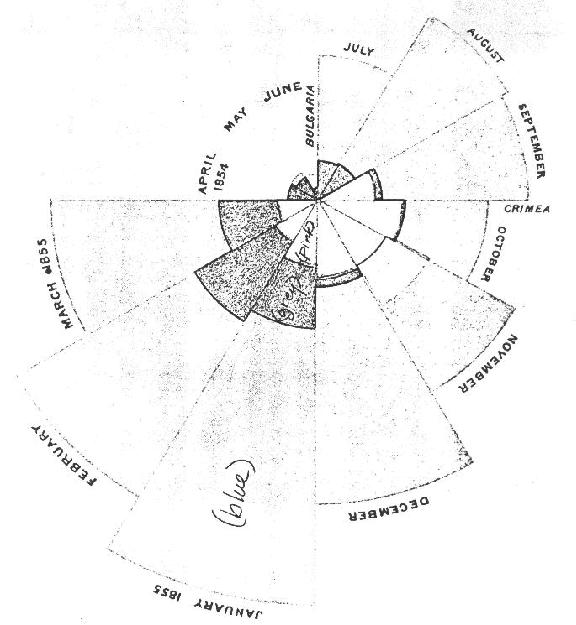

Throughout ut military history until

the 20th century the main cause of death in war was disease rather than

wounds sustained in battle, and the Crimean War was no exception. Nightingale’s

numbers still speak eloquently. During the first months of the Crimean

campaign there was “a mortality among the troops at the rate of 60 percent

per annum from disease alone,” a rate exceeding that of the Great Plague

of 1665 in London and higher also “than the mortality in cholera to the

attacks” (that is, the mortality among those who had contracted the disease).

In January, 1855, the mortality in all British hospitals in Turkey and

the Crimea, measured in relation to the entire army in the Crimea but not

including men killed in action, peaked at an annual rate of 1,174 per 1,000.

Of this number 1,023 deaths per 1,000 were attributable to “zymotic” disease

(a category introduced by Farr including epidemic, endemic and contagious

disease). This means that if mortality had persisted for a full year at

the rate that applied in January, and if the dead soldiers had not been

replaced, disease alone would have wiped out the entire British army in

the Crimea.

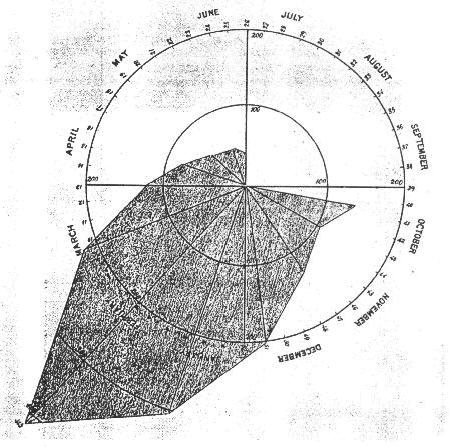

Nightingale’s various methods

of calculating mortality dramatized both the impact of disease and the

effects of improved sanitary conditions. Calculated on an annual basis

as a percentage of the patient population, the death rate at the Scutari

hospital reached an incredible 415 percent in February, 1855. In March,

however, Nightingale’s sanitary reforms began to be implemented and mortality

among the patients declined precipitously. By the end of the war, according

to Nightingale, the |

death rate among sick British soldiers in Turkey

was “not much more” than it was among healthy soldiers in England; even

more remarkable, the mortality among all British troops in the Crimea was

“two-thirds only of what it [was] among our troops at home.”

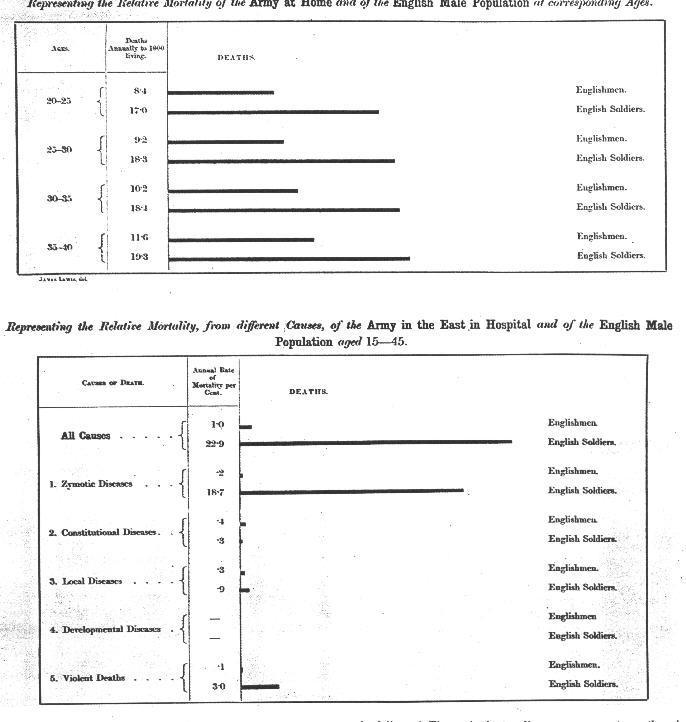

The comparison suggested that

the soldiers at home were living in their barracks under unhealthy conditions.

After Farr had made Nightingale aware of the significance of mortality

tables, she at once thought of comparing the mortality among civilians

to that among soldiers. She found that in peacetime soldiers in England

between the ages of 20 and 35 had a mortality rate nearly twice that of

civilians. It is just as criminal, she wrote in 1857, “to have a mortality

of 17, 19, and 20 per thousand in the Line, Artillery and Guards in England,

when that of Civil life is only 11 per 1,000, as it would be to take 1,100

men per annum out upon Salisbury Plain and shoot them.” (The 1,100 represented

20 per 1,000 of an enlisted force of 55,000.) Clearly the need for sanitary

improvements in the military was not limited to hospitals in the field.

By pressing her case with these statistics Nightingale eventually gained

the attention of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, as well as of the prime

minister, Lord Palmerston. In spite of the passive resistance of the War

Office, Nightingale’s wish for a formal investigation of military health

care was granted in May, 1857, with the establishment of a Royal Commission

on the Health of the Army.

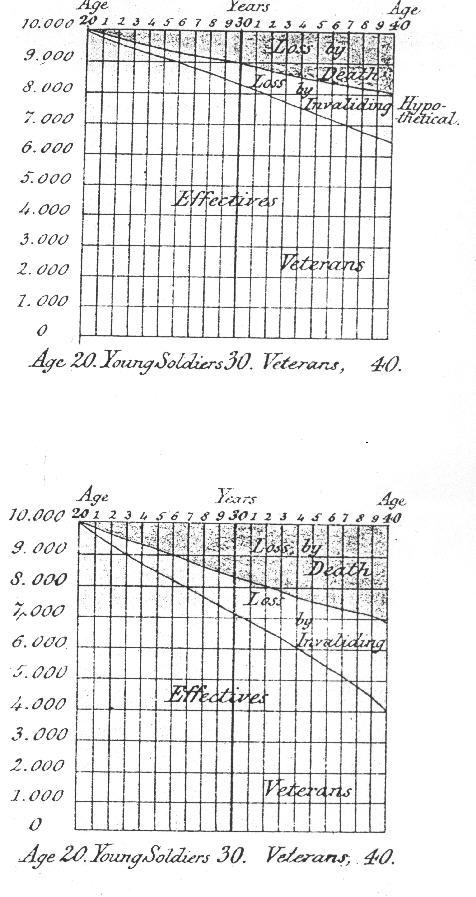

It would not have been possible

at that time for a woman to serve on such a board. Nightingale nonetheless

strongly influenced the commission’s work, both because some of its members

were her friends (including Sidney Herbert, the minister who sent her to

the Crimea) and because she provided it with much of its information. As

a statement of her own views she wrote and had privately printed an 800-page

book titled Notes on Matters Affecting the Health, Efficiency and Hospital

Administration of the British Army, which included a section of statistics

accompanied by diagrams. Farr called it “the best [thing] that ever was

written” either on statistical “Diagrams or on the Army.”

Nightingale was a true pioneer

in the graphical re presentation of statistics: she invented polar-area

charts, in which the statistic being represented is proportional to the

area of a wedge in a circular diagram. Nightingale used these diagrams,

which she called her “coxcombs” because of their vivid colors, to dramatize

the extent to which deaths in the Crimea campaign had been preventable.

Farr was impressed with Notes, and much of Nightingale’s work found

its way into the statistical charts and diagrams he prepared for the final

report of |